I was given the opportunity, early in 2014, to travel to the Great Pacific Garbage Patch to investigate the possibility that groups of American migrants had begun to settle there. What follows is a sordid look into one of the most ravaged and polluted locales on the Earth, a place as inhospitable as the Atacama desert and as merciless as the jaws of Everest.

Note From the Author: Because of certain national and international legal issues I cannot reveal the names of the people who brought me to the Garbage Patch, their method of transport, or for that matter any information that might identify them in a court of law.

Somewhere at the Edge of Civilization

Environmental scientists have come to believe the trash islands began to form at some point in the 1980’s. Others have suggested their formation might date as early as the 1860’s, when snake-oil tradesmen were known to dump crates of unsold medication into the Pacific Ocean. Despite these minor differences, most leading environmental scientists and marine biologists agree that the Garbage patch is the work of human beings; composed from the refuse of the great coastal cities of the pacific and the liners and trawlers that travel between them. A small minority opined that the islands are a natural, albeit newly formed, aquatic habitat created and maintained by fish and other marine life.

My study, however, had little to do with the squabbles of environmental scientists and Garbage Patch denialists. I was to spend a week investigating rumors that suggested the trash islands had been settled by desperate émigrés from the American mainland. In 2011, an article in the New York Times estimated “as many as one million American citizens may be residing illegally on the Garbage Patch.” Another report, published by The National Review for Marine Life, suggested the estimate published in the New York Times was vastly overblown. The Review speculated the trash islands were incapable of sustaining more than ten adult human beings at any given time. I was sent to put to rest an argument the same New York Times article declared, “…is tearing both the scientific and non-scientific communities apart.”

Arrival

A friend from Newfoundland suggested I charter a ship from Mexico to the Garbage Patch. There is less resistance, he said, from the Mexican government towards trash island explorers than the United States, which patrols the waters between California and the Garbage Patch with heavily armed FEMA gunboats and attack helicopters. Unfortunately — because plane tickets to Tijuana were unreasonably expensive — I was forced to take the Greyhound bus to Oakland so I could depart from there. It was important then to charter a [safe] and [legal] voyage to the island. The [people who took me to the Garbage Patch] were [very nice] and [completely unarmed]. They had a long history of [transporting legal goods] between California and Southeast Asia. [None] of them were felons.

One of [the people who brought me to the island], a man with dry pale skin and whiskey on his eyes — who, for the sake of anonymity, will be called Bob — convinced me to shorten my stay on the island.

“You need to understand,” [Bob] said. His voice was dry. “That island is full of shit and wreckage. There’s nothing to eat there that won’t give you diarrhea and things. Things I reckon is worse than diarrhea. Do you have a problem with diarrhea? With things I hear is worse than diarrhea?”

I told him I did. He stroked his chin as he considered my words. Then his eyes lit up like a shot of caffeine and he told me to wait while he went to get something. He wandered down the stairs [of the thing we came on]. He came back with a paper bag; white and darkened by moisture.

“You’re gonna need this,” he said, and passed it to me. Inside was a B.M.T. from Subway; an Italian B.M.T. on 9-Grain Honey Oat bread. He said, “This is a B.M.T. from Subway. An Italian B.M.T. I got it with a coupon in San Juan.”

“That’s a long way for a sandwich,” I said. I leafed through the sandwich. It looked fresh enough; the vegetables were soggy but the meat had held up well.

“Yeah,” he said. “Some eight-thousand or so miles, I reckon.”

I asked, “Are there any mushrooms on it?”

“You want some mushrooms on it?”

“No.”

“I’ve got some mushrooms in a cooler,” [Bob] said and took the B.M.T. from Subway. “Hold on a bit.” When he came back there were mushrooms on the sandwich.

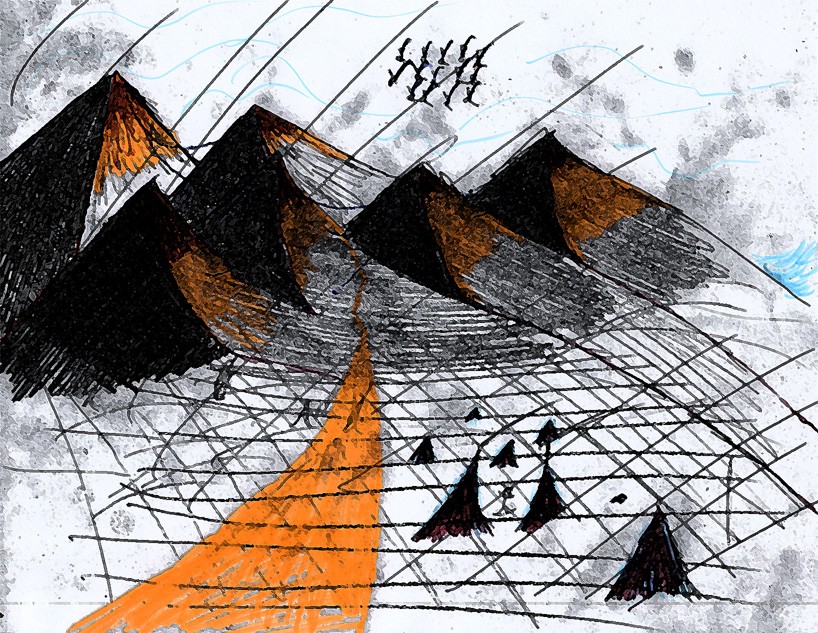

[Bob]’s warnings of diarrhea and his subtle allusion to dysentery convinced me to scale back the trip. I would instead conduct my research over the course of three days. We pulled up to a small peninsula on the southern coast of the island. Even from [the thing we came on] I could see the silhouettes of great hills and mountains rising in the far north. The island stretched into the west as well, with small hills and mesas dotting the landscape. In a traveler’s backpack I carried a gallon of water, a box of peanut and chocolate Kind Bars, a box of latex gloves, an environmental shawl I had found in the bathroom of a Menards, and a two-way radio to maintain contact with [the thing I came on]. In a smaller pack I carried a Polaroid camera and a pair of ski goggles. I also brought an umbrella in case of adverse weather. I had not anticipated the necessity of the umbrella until an hour before the departure of [the thing I came on] and bought an eight dollar umbrella from Walgreens.

Before I set foot on the Island, the [general manager] of [the thing we came on] approached me and said, “If you’re going on that island, you might want this.” He gave me an enema.

“Thanks,” I said, and put the enema in my backpack.

The Island

The ground — a patchwork crust of tires, dirt and plastic bottles — depressed like a sponge under the weight of my boots. Where there would have been bushes and trees on the mainland lay asbestos ridden sofas and rusted street lights. Ancient buses and trolleys stood from the ground with defunct tugboats while the skeletons of dolphins, whales and pacific salmon shaped the land and defined its structure. The wind was strong. Violent storms swept acerbic dust and discarded wrappers from Snickers and Twix bars across the landscape and against my face. I covered myself with the shawl and wore the ski goggles over my eyes. I brought the umbrella out too, but it was all but destroyed in the windstorm; the billions of sand particles wore the thing down to its frame.

Once the storm had calmed, I walked for several hours to the north of the peninsula collecting samples of garbage, dead fish, some strange mutant insects, and some long forgotten parking tickets. Most of the parking tickets were from Los Angeles. I took these samples to a small plateau where I had good light and a good view of the surrounding region and took some pictures of them with the Polaroid. The plateau overlooked a long and desolate region of tire filled badlands. I could see a man standing half a mile or so to the west of the plateau.

I carefully approached the man, so I would make no sound that might alert him, and rummaged through my pack for the Polaroid. The man was fishing. He wore a ragged coat that might have been made from the skin of a whale and had strung to it the bones of fish and the shards of glass bottles. He had wrapped a purple feather boa around his balding sun-burnt head so only a few strands of bleach blond hair hung down to his shoulders. He had a jar of teeth tied to his belt. A small pile of purple and red fish lay next to him. Most of their scales had peeled from their flesh.

He had just reeled a fish from the hole when I found a good angle and took a picture of him. He heard the camera and spun around to face me, the fish falling off its hook and back into the hole. He pulled a transparent enema from the inside of his coat and aimed it at me. It was filled with something I do not care to describe.

“You ought not to sneak up on me like that,” he said, his voice throaty and deep. His face was burnt and his skin sagged beneath his cheekbones. He looked into the fishing hole and then back at me.

“Uh, hey,” I said. “How’s uh, how’s it going?”

“What? You should watch yourself sneakin like that. Makes people nervous when people come sneakin around their backs with Polaroid cameras and things like that.”

“Yeah.”

“You lost me a fish,” he said, “you want to make it up to me or something?” He looked me over, his eyes bloodshot. He sniffed a bit. I was surprised he could smell anything over the stench of the island.

“I have some Kind Bars,” I said and tossed a Kind Bar to him.

He caught it, “You have any Cliff Bars?”

“No. I don’t like those.”

He shrugged, “I’m more of a Cliff Bar man myself.”

“I’m not a fan,” I said. “They taste like paste.”

He lowered his enema, “Paste?” he shrugged again. “I thought you were Silky for a minute, when you snuck up on me. You’d be surprised how sneaky Silky can be. You kinda look like maybe what he might have looked like when he was a bit younger and less melty.”

I said, “I don’t know Silky.”

“Spose you wouldn’t. He’s still wretchin’ I think from those mushrooms he ate,” he looked into his fishing hole contemplatively. “You ever tasted paste?”

“I’ve had Cliff Bars.”

He looked back at me, “Cliff Bars are like bricks. Kind Bars not so much. You know what you’re gettin’ with a Cliff Bar.”

“Alright,” I said.

I told him why I came to the Garbage Patch. He told me his name was Herb and that there was a town called New Scenic on the west coast of the island. It was named after Scenic, South Dakota. Its founder, Robert Turnami, had been born there. He said he was headed there, and if I was interested in learning anything about the people of the island, I should go with him. It wasn’t far, he said, just a four hour walk to the west. I waited with him for another hour while he finished fishing. He looked into the hole and shook his head.

“Usually,” he said, “there are better fish around here.”

Scenic

Herb told me he had been brought to the Garbage Patch by FEMA after being detained for sleeping in a subway station in Manhattan. It was a painful transition, he said. He was brought to the west coast in a van cramped with homeless men and some unfortunate jaywalkers. When the van stopped the FEMA workers placed each of the men into a barrel and rolled them out to sea. He spent several weeks in the barrel before he washed up on the coast of the Garbage Patch.

Despite his personal experience, he said it was a mistake to think everyone who lived here had migrated unwillingly. The mayor of New Scenic, a man named Joshua, supposedly moved to the Garbage Patch of his own accord. Herb did not know why.

We stopped half way to take a rest and to split a Kind Bar. Herb pointed towards a mountain range in the northeast that dominated the horizon, “They say there’s a Hardee’s,” Herb said, “on the other side of the island, past that mountain over there. But that’s deep in gull country. Nobody’s ever come back.”

“Do you ever hunt the gulls?” I asked.

“What?”

“For food?”

Herb shrugged, “What? Are you trying to start a war?”

I didn’t have anything to say to that.

Herb stared off into the east and said, “You’re headed back to the states after all this?”

“Yeah,” I said. “That’s my plan.”

Herb pulled an old photograph out of a pocket in his coat. It was a picture of a small child, smiling, with singed blonde hair and a one tooth grin. He was waving his arms in the air. Herb was standing behind him with a lit butane torch.

“That’s my son — Goober,” Herb said. “I think he’s awful mad with me.”

“Why?”

“It don’t really matter,” Herb said. “You know, if you ever see him…he’s still in the states…can you do me a favor?”

“What’s that?” I asked. He gave me the photograph.

“Tell him I’m sorry about settin’ him on far.”

“Setting him on what?”

“Settin’ him on fire.”

“Where is he now?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” Herb sighed. “Somewhere in Nebraska I’d guess.”

“I’ll check the Yellow Pages.”

“You bring him that photo. Tell him that I miss him, okay?”

“Yeah, I can do that,” I said. We packed up and left a few minutes later.

The land had changed from the dry flatlands of the east to rolling hills of disposed tires. Some of the hills were small and defined by gentle slopes, and others punctuated the landscape with their height. I had to climb slowly so as not to lose my footing.

“The town is just over this hill,” Herb said as we climbed one of the larger mounds. I was lagging behind him. Shards of glass were embedded or lying on most of the tires, and it would have been easy to cut my hand. Though I might have just been acclimating, it seemed to smell better in this region of the isle. There was a vague scent of cinnamon on the breeze.

I climbed the mound of tires, careful not to cut my hands on the glass, and caught up with Herb at its summit. The mound overlooked New Scenic: a small collection of huts built around a fishing hole on the western coast of the island. The locals had built a wall of tires and corrugated metal around the town, a measure Herb explained was to keep out the gulls.

“Can’t they just fly over them?” I asked.

Herb shook his head, “Gulls don’t like confined spaces. The walls keep them out good.”

We descended the mound and approached the gate. It was a sheet of corrugated metal with seashells strung over it. The man who greeted us held a harpoon gun and wore a diving suit and a vest made from an old fishing net. He pointed the harpoon towards us.

“You know I can’t let you in while you’re packing,” he said to Herb and mimed the use of an enema. “And who’s this? Is he armed too?”

“You know me, Pete,” Herb said to the guard and slapped me on the back. “This here’s a friend. Saw him near my fishing hole.” Herb said and gave Pete the enema.

“What did you put in this?” Pete looked at the enema.

“It’s an [obscenity],” Herb said. “I just took some [obscenity]… filled it with milk and then [obscenity]…[obscenity] it’s skin fell off an I hung it up with an [obscenity] and ground that down…mixed it up with a quarter cup of water real good…”

“Yea, oh wow,” Pete said. “That’s awful. Yeah. That’s horrible.”

I gave Pete my enema.

Herb said, “Don’t mix mine up with his.”

“I don’t think I’ll have a problem with that…” Pete said and kicked in the gate. Then he turned to us and said, “You can go in now.”

Herb led me through new scenic. The streets were paved with old bricks, plastic bottles, and some aluminum cans. There were unlit torches every ten feet for when it would get dark. The houses and the shacks were built from a variety of materials. Some were made mostly from tires, while another had been built out of glass bottles. Another was built from plywood. Herb said he wasn’t sure where the plywood had come from or why it had not rotted away.

Regarding the hole, Herb said, “Fish just swim under that hole and die. Then we can scoop em out.”

“But you have your own hole for fishing,” I said.

“The fish here are already dead so they’re no good,” Herb said. He wiped his face with his palm. “They just die there and then float up to the top. Makes them real easy to grab. If you walk a little bit inland there’s this area where there’s better fish without all the plastic bits sticking out of them. They taste better and are easier to cook cause you don’t have to worry about the plastic bits melting.”

The other residents of New Scenic didn’t seem to have too much of a problem taking fish from the hole. They would take big nets — some of which were real fishing nets — and drag as many fish as they could from the water. Sometimes they’d pull out a squid or a dolphin. Sometimes they’d pull out a shark. Herb told me sharks and dolphins were the most prized because they gave a lot of meat. Whales were despised because if one died it could block the hole.

The citizens of New Scenic were not great examples of health. Herb, because of his diet, was among the most physically fit. Most of the other denizens were missing limbs, chunks of flesh, or clothes. Many had stretches of exposed muscle and bone on their arms or their legs. While we were there a man’s jaw fell off. He kicked it in the hole and yelled, “Euggghhhh!” Some of his upper teeth came out and Herb collected those and put them in his jar.

Herb was bringing me to Joshua, the mayor of New Scenic. He lived in a longhouse built from the skeletal frame of a blue whale. It had been covered in rugs and sheets and tarps Joshua and his people had found and strung together. The foyer had plastic tile flooring, a small fountain made from a bicycle and a rubber hose, and a mayoral desk. Joshua sat behind the desk; a sheet of copper held aloft by four stacks of tires that had been melted together.

“This is where Joshua lives,” Herb said, and then left me inside.

Joshua

Joshua was dressed like a transient prince, his whale-skin jacket glossed and adorned with glass marbles and red, blue, and yellow beads. His hair was long and black and his beard draped past his legs and over his feet. His skin was a bluish color, and it was pockmarked and covered in sores and thin scars. He must have lost both his hands at some point because they had been replaced with long hooks, the left a traditional prosthetic hook and the right a makeshift thing fashioned from the handle of a car door. Where his face was wrinkled it would almost split. He moved like glass.

“Hi,” I said. I introduced myself and briefly explained why I had come to the Garbage Patch.

Joshua turned towards me slowly, “Well, you can see that there’s not much here of interest really.” The skin of his face cracked as it moved.

“Huh, uh, so what made you come here?” I asked.

“What made me come here?” As he spoke one of his eyeballs slid from its socket and onto the floor. “Ah shit…”

I watched the eyeball roll.

“You alright?” I asked.

“I’ve seen worse?” Joshua shrugged and stood up from his desk. “Can you grab that for me?”

“I don’t think so,” I said. It looked like the eyeball had picked up some dirt from the floor.

“I don’t have any hands.”

“Yeah,” I said. “That’s true.” I put on a pair of latex gloves and picked up his eyeball. He carefully balanced it on the tip of his hook and slipped it back inside its socket.

“Thank you,” Joshua said. His eyes moved fluidly now. “What you see here, is the conclusion to living in a place like this.”

I asked again what brought him here.

“Well,” he sighed and sat back down at his desk. “A couple of years ago, I was eating Cheerios and I was saving up all the box labels. If you mailed them back to the company they’d send you a watch with all the Peanuts characters on it. Later, I was cleaning up my apartment and I must have thrown them all out. ”

“Did you find any of them?” I asked.

“Yeah,” he said. “I found a couple. But by that time it was too late to send them in.”

“Why’d you stick around?” I asked.

Joshua shrugged and tapped his hooks against his desk. He looked up at me and said, “I dunno, maybe one of those watches washed up here.”

The Locals

“You can find almost anything you want out here,” said Gummy, New Scenic’s resident physician.

We met at the Gypsum Batch, a small diner set up in a school bus near the harbor. The door sign reminded customers to bring their own silverware and a spare set of teeth. Nothing on the menu looked appetizing so I ordered a cup of coffee. The coffee wasn’t good but it was better than what I keep at home.

“Adderall, cocaine, Viagra, Oxycontin, even morphine — people throw this stuff out all the time and it winds up over here,” Gummy said. “It gets in the fish too. If you eat the fish you get pretty high. But you only want to take the drugs if they’re sealed up good. If the seawater’s in there you’ll be dehydrated real quick.”

“That’s really interesting Gummy,” I said.

Gummy was the first resident I spoke with after I met Joshua. He specialized in collecting discarded drugs and prescription medications. It was his job to distribute those drugs equally and freely to the population and those who chose to visit. I chose not to take any of his drugs for a number of reasons.

“People throw out all kinds of weird shit,” Gummy said and showed me a bottle of pills. The label had dissolved. Somewhere in the ocean, presumably. “I’m pretty sure these are sugar pills. I can’t speak with any certainty on that. I mash them up and use them as a sweetener for the fish sometimes. If you want to eat the fish here you need something in between for flavor.”

I asked, “Do flavor packets ever float your way?”

“What do you mean?”

“Ketchup. Honey-mustard. Blue cheese?”

Gummy rubbed his chin, “We get honey-mustard sometimes. Never find ketchup. I’ve found ranch here and there. It usually washes up a bit south. I’ve seen Caesar a couple times but he’s not very consistent. If you dig anywhere you’ll eventually dig up a can of Velveeta. I think it might be what keeps the island afloat.”

“What’s the most important thing that washes up?”

“Water bottles. People throw them out all the time. Sometimes they’re even sealed. God bless them, god bless those people,” he said. “If it wasn’t for them, we’d never make it. Never. If billions of unfinished bottles of Dasani, Ice Mountain, and Fiji water, uh, you know, didn’t wash up here every couple weeks, we’d really be fucked.”

Next I spoke with a local craftsman named Benjamin, who was — at least for New Scenic — well dressed. He couldn’t meet at the Gypsum Batch, my contact said he’d be busy working on his car all day (which sounded interesting), but he’d could spare a couple of minutes for an interview at his workshop.

The workshop was sort of yay-high, of so-so width, and was built from assorted materials of a nondescript nature. Benjamin stood near the entrance in a dirty sports jacket, ripped khaki pants, and a tattered satin tie. I was told he had once been a wealthy entrepreneur and adventurer who did business between Bangladesh and Hong Kong. His days of wealth came to an end on a business trip in 2011 AD, 200 nautical miles south of Maui, when some of his colleagues threw him off their yacht. The currents of the ocean left him beached on the shores of the Garbage Patch.

He had scavenged car parts from the Island to replicate a 1969 Ford Mustang. Unfortunately, he didn’t have any gas.

“If we were in the gulf,” Benjamin said, “this would be a whole different story.”

I asked which Gulf he meant.

“Probably any of them, actually, now that I think about it,” he said. “Here take a look at my Mustang.”

He showed me his Mustang. I was impressed; it almost looked like a Mustang. It was only the windshield, rear view mirrors, hubcaps, and steering wheel that remained missing. And the gas, of course. Otherwise it was almost complete. I didn’t have anything to say or ask about the mustang though, like how he got it the parts, or what he planned to do with it, or why it looked like he was trying to use handlebars in place of a steering wheel — hindsight is 20/20. So I asked him how it was that one could survive, even thrive, in this harsh environ.

“It’s a tough way of living,” he said, clearly disappointed I didn’t ask about his car. “But every day is just another kind of routine. It’s not much different than it is stateside except there’s no electricity, you have to fish — you have to eat it too — every day, you have to find new ways to entertain yourself, the ground is made of garbage, and even a small cold can kill you. It rains really hard sometimes. I’ve seen some houses people built actually melt in that rain.”

He shrugged and looked despondent for a moment.

“So I guess, really, it’s not much like, you know, the mainland at all,” he said.

I asked how it was someone’s house could met.

“You need to be careful with what you make your house out of,” he said. “You can’t make your house out of something that melts.”

I had yet to see any women in New Scenic so I asked Benjamin about the demographics of the town and of the island.

“I think,” Benjamin said. “I think they must be on a different island. I don’t think FEMA wants us to reproduce.”

“What’s FEMA’s deal around here?” I asked.

“FEMA?” Benjamin shrugged. “Who said anything about FEMA?”

“What?” I asked. “You just said they didn’t want you reproducing.”

“No, no, no, no. You must have misheard me,” Benjamin said. “There could be women all over the place. I don’t know. Certainly has nothing to do with FEMA.”

I prodded Benjamin about FEMA for a while but he refused to give me any useful information.

The most peculiar man I interviewed was ancient and small and went by the name of Silky. He lived in a mound near the center of town and we met there because he could no longer move. At least, I thought it was a mound but it wasn’t. I’ll never know, for sure, what it was. But it was there that we met.

His head was shaped like a square of tofu and sat atop a short body that dissolved into the ground like a tree stump. When he spoke, he’d talk with bright red gums full of canker sores. He had no teeth and he had no lips either, his skin looked like a marshmallow, and he was clothed in a single grey rag with a hole on top for his head to poke from.

Silky spoke fast. Volumes of saliva dripped from the corners of his mouth.

“I came here in the summer of oh-eight, right when I was full of hope,” he said. “Some men came and they put me in a choke hold and then they put a collar on my arm and then they put me in a barrel and then they put me on a river and then I washed up in Mississippi. But nobody ever told me where Mississippi was so I got lost coming back.

“So I walked back to San Francisco where I was stayin’ underneath,” he took a deep breath, “the bridge but this time the guys came they picked me up and and then they put me in a barrel. ‘What you doin’ back here,’ they said all at once like they were three of them or something. I told them I didn’t even know how I got here and then they put me out to sea and then I was here. I didn’t know what I was going to do cus I didn’t see any food for miles out here and these gulls were swarmin’ around right. If I hadn’t of run then they might have poke out my eyes and reached into my brain and all that.”

“I don’t think Seagulls can do that,” I said.

“I used to think like you,” Silky said. “I think I used to look like you…back before I started eating all this fish.”

“I don’t know about that,” I said.

“Yeah,” Silky said. “I used to look just like you. You’re gonna look just like me some day.”

“You think?”

“Anyway,” Silky coughed. “I thought I was gonna die here, seeing as I can’t walk too good, but the good folks in Scenic found me and they were having a really bad bout of dysentery. Me, I’ve had dysentery for ages before I came here and I know what to do with it so I taught them a thing or two about dysentery and they helped me out finding foods and things.”

“Thank you,” I said. “That’s really all I need.”

Silky grinned. He looked pleased with himself.

“Say,” he looked at my backpack with watery eyes. “You don’t have anything to eat do you? I’m right tired of all this fish.”

I looked in my backpack. I had the Kind Bars and the B.M.T. from subway but I doubted that he could eat either of them.

“Have you ever had a Kind Bar?”

“What’s that?”

“It’s full of nuts,” I said and showed him a Kind Bar.

“Nah, I can’t eat that. You have anything else?”

“I have a B.M.T. from Subway.”

“You wouldn’t mind if I had a bite of that B.M.T. from Subway, would you?”

“You can have the whole B.M.T. from Subway,” I said. “I don’t want it.”

Silky seemed appreciative.

A Visit to the Doctor

Silky died fifteen minutes later. He began to wretch violently after he ate the B.M.T. from Subway. Despite the best efforts of Gummy, Silky’s dysentery worsened and he entered a deep state of diarrhetic shock. At 3:58 PM Silky fell into a coma. Gummy responded quickly and administered a lethal dose of morphine. When asked to comment Gummy shrugged.

“He looked pretty fuckin’ dead to me,” he said.

The Funeral

Gummy slid Silky’s body into a large plastic bag he had found in the town’s pantry. The bag wasn’t long enough to cover Silky’s head so Gummy covered it with a towel. The townspeople gathered around Silky’s house and Herb, Gummy, and Pete laid him on a large piece of wood and carried him out to a little plaza near the hole. Some of the people gasped when they saw him, lifeless, on the plank.

“Just yesterday he was alive and breathing,” one of them said. “It must have been those mushrooms he ate yesterday. His wretchin’ was keepin’ me awake but I never thought it would be the end of him.”

Another said, “He knew he couldn’t eat mushrooms. It’s just too bad…he never knew what was good for him.”

Herb leaned over to me and said, “People were awful fond of Silky. He was a voice of reason to us. People are gonna be awful broken up about this.”

“That’s really terrible,” I said.

“You were the last one who talked to him right?” Herb asked. “What were his last words?”

“Uh, ‘You wouldn’t mind if I had a bite of that B.M.T. from Subway, would you?’ Those were his last words.”

Someone asked, “A B.M.T. from Subway?” It was a one-armed man in a red shirt wearing a dirty white baseball cap. “Did he finish it?”

“Yeah,” I said. He seemed disappointed. “What happens now?”

“We gotta take him to the graveyard,” Herb said. “We gotta take the boat. Graveyard is a ways off in the no-man’s land between here and gull country.”

I helped them carry the plank with Silky’s corpse to the westernmost point of the town, where there was a small dock with a rather large raft made from plywood, recycled plastic, and countless multicolored pool noodles. Silky’s head rolled back and forth across his shoulders as we lifted him onto the raft and drove a hook through his plank so he wouldn’t slide around the raft. When we had secured him on the raft Joshua came to the little pier and said a few words for him in front of the crowd. He stepped back and let the town guard conduct a twenty-one gun salute with their enemas. When they had finished Joshua left the pier and most of the townsfolk followed him. Herb, Pete and I were left alone on the pier.

“He’s not coming with us.” Pete said to Herb and pointed at me.

“Nah,” Herb said. “He’s not gonna want to do that. I reckon he’s had enough of death today.”

I told them I’d go.

“You can’t go,” Pete said to me. Then to Herb, “Go get Gummy.”

“Why not?” I asked.

“It’s bad luck. The gulls can smell an outsider for miles,” Pete said and fastened another hook to Silky’s plank.

“That’s just a bunch of superstition, Pete,” Herb said. “Let’s take him with. He’s been a good enough guy.”

“Okay,” Pete said. “But we leave at the first sign of trouble.”

Pete gave us back the enemas. Mine was still empty, Herb’s was still full. We got on the raft and left New Scenic.

Somewhere Along the Coast

We were going north. I was surprised by how smoothly Herb and Pete maneuvered the raft along the coast. They rowed gracefully and pulled the raft through the water and over each wave and away from the shore, which would at times seem only like inches to my right. We passed jagged cliffs and garbage spires floating loosely along the coast. The waves would crack and spit and throw themselves upon our raft and upon the cliffs.

It was my job to hold Silky’s body in place. Were he to roll off his funeral plank he might disrupt our weight distribution about the raft. I knelt over the hill of his stomach and pressed his shoulders and his arms against the hull. The crest of each wave would jolt the small craft. I feared at any moment one of the noodles would come loose and the raft would come apart and all its bits would be strewn across the foamy sea.

Hours passed on the raft. My legs became sore and I felt the muscles around my knees and elbows turn wet and numb. The wind was cold and salty and it would sting my skin and my eyes. Sometimes I would feel ill. Sometimes a large wave would push water over the little bulwarks of the raft and either Herb or Pete would have to stand up to grab a small bucket to toss the water overboard.

The sun had started its descent when I heard Herb shout, “That’s it. We’re awful close now.” I tried to turn my head to see the shore but I couldn’t look behind without letting go of Silky’s shoulders. Silky was heavy and he was decomposing quickly. Every time a big wave hit the raft a little chunk of him would slip out of the bag. Sometimes it would be a finger, sometimes a little bit of his legs or his belly. I feared nothing would be left of him by the time we got to the graveyard.

“Listen, you, back there,” Herb said. I assumed he was talking to me. “Sometimes the gulls get hungry. They got a taste for man blood.”

“That’s okay,” I said.

“We’ll be safe,” Herb said, and he must have pointed to something, I assume his enema. “This can melt this skin right off a gull’s little wings.”

Pete yelled, “Don’t feel so confident Herb. I feel better with you around but don’t let whatever is in that enema get to your head.”

“That’s nice Pete,” Herb said. “I reckon we see eye-to-eye on a lot of things.”

Herb was quiet for a bit. Then he said, “Hey, you back there!”

“Me?” I asked.

“Yeah. Can you hold this for me?”

“What is it? I asked. I heard Herb roll something to me across the raft. It was his jar of teeth. I picked it up and put it in the breast pocket of my jacket, “Yeah I said. I can hold it.”

“Thanks,” Herb said.

I asked, “Do either of you know anything about FEMA being here?”

“They put me in a barrel,” Herb shrugged. “They killed [unprintable] back in [unprintable]. Saw that with my own two eyes.”

“They killed [unprintable]?” I asked. “No way!”

Pete yelled, “Don’t believe everything Herb says. Especially about [unprintable].” The wind had suddenly picked up and the Ocean became very turbulent. The raft swayed like a rum-drunk elephant as the wind beat at my ears.

“Say what you want, Pete!” Herb yelled. “I know what I saw. And it was awful shameful what they did to [unprintable]. You wouldn’t believe it, but they — and them whole government — are controlled by the Hmong…”

The Graveyard

We hit the shore an hour later. The craft jolted and we pulled it onto the beach so it wouldn’t drift away while we were gone. We carried Silky’s body out of the raft and brought it through a narrow crevasse (to, “avoid the gulls”) where bits of plastic and metal would stick out from the walls. The land here was dry and brown and the garbage seemed to have eroded and hardened into a material not unlike sandstone. We couldn’t fit Silky through the most narrow point of the crevasse. We had to take his body out of the bag and remove the legs and the arms to fit the body through. When Herb and Pete had finished bringing Silky’s head and torso through the stretch I brought the arms and the legs and we reassembled them in the body bag.

The graveyard lay at the end of the crevasse in a pit filled with bones. The bones were covered in rags and trinkets. There were no tombstones and there were no markings of any kind that would identify the deceased. We lifted the plank and slid Silky into the pit. His body came out of the bag in many pieces. The towel and his head came off at the same time.

“Well…that’s that,” Pete said and looked upon the stillness of the mound. “Do either of you have any last words for him?”

“Yeah,” Herb said. “Uh…goodbye Silky. It was awful nice hearing your stories and all. I hope that you have a good time out here.”

Pete looked at me, “And what about you?”

“I didn’t know him very well,” I said.

“Well, that don’t change nothing,” Herb said. “You were the last one to talk to him. You should have something to say.”

“Alright,” I said. I looked down at Silky’s head. One of his eyes was missing, his nose was gone and he looked like he was frowning. “Well…it was good talking to you Silky. You know, I don’t think you really looked like me but I guess if it makes you feel better at all I can say that you did.”

“Okay,” Pete said. “that wasn’t too bad. We all made peace with him.”

Herb said, “Yeah, you do look an awful bit like Silky when he was younger.”

The Gull Sound

A tiny white “v” appeared on the horizon and swooped upon us with great speed. It rolled upwards, back into the sky, and then dove again. I looked behind and saw Herb reach for his enema and aim it high, but as he did so another gull dove towards him like he was little more than worm on a beach. Pete aimed his harpoon gun and fired but the harpoon missed its target and fell into the graveyard. The gull went straight into Herb’s head. The beak…[unprintable]…the whole gull came out the other side of his head.

It was an ambush: a swarm of gulls had descended upon the graveyard. I started to run and Pete shouted to me I was going the wrong way. I ignored him and kept running. I heard Pete’s fevered footsteps over the laughter of the gulls, their incessant “au ahs” and their warlike screeching. I heard Pete trip behind me but I kept running. Only when I was far enough that the gull sound had diminished did I look back. I saw what might have been thousands of gulls pecking at the ground but I didn’t see Pete.

“Jesus Christ!” I said.

I Found a Cave

I ran until I found a small cave in the landscape. It was rocky and full of candy wrappers and shards of glass dulled by erosion. The gulls were in the distance. They must have been preoccupied with their catch. I decided to stay there until it was dark, when the gulls would hopefully be going to roost. I dug into my survival rations. I was going through the Kind Bars too quickly. I knew I shouldn’t have bought the chocolate ones. I have no self control.

The cave was small and only dimly lit near at the entrance by the sunset. I went to lie down and I set the alarm on my phone to go off just before dusk. I looked at the picture of Herb’s son, Goober. I knew then I had to live to tell this child about his father. He’d never believe a seagull went all the way through his head.

Gull Country

I called [the thing I came on] with my two-way radio. [The general manager] picked up.

“Hey, how’s it going?” he asked. “Enjoying the island?”

“Not really,” I said.

“We can pick you up whenever, you know.”

“I don’t know about that,” I said. “The gulls are after me.”

“The gulls are after you?”

“Yeah; the gulls.”

“What happened? Are you in gull country?”

“Yeah.”

“What are you doing in gull country?”

“Uh, there was a funeral, and then the gulls ate the other guys…”

“They ate them?”

“Yeah,” I said.

“Jesus Christ.”

“That’s what I said.”

[The General Manager] of [the thing I came on] told me I needed to find a landmark he would be able to spot from [the thing he was on]]. He said the gulls were, “very vicious,” and “generally full of surprises.” He told me I should call him with the two-way radio once I had found a suitable landmark where I could hide.

“We’ll use the radio to get your coordinates,” he said.

“Cool.”

He asked, “You think you can do all this?”

“I can do that,” I said.

“You can?”

“Yeah?” I said.

“What?”

“Sorry,” I said. “I was just saying, ‘yeah.'”

“Okay then,” he said. “I’ll see you later.”

“Alright,” I said. “Bye.”

I crept out of the cave. It was crisp outside. The stars were out and I could see the band of the Milky Way high above me. I started walking immediately. I stumbled upon a ravine and followed it to the east. Gull country was different than the rest of the island. It was cleaner and didn’t smell. It seemed like the gulls had eaten, broken down or re-purposed most of the garbage. It looked as if most of the paper trash had been carried off. I figured the gulls must have been using it for their nests.

The mountain range I had seen before, when I first arrived on the island, was just to the south now. The foothills were dotted with the nests of gulls, and cast from each was a pinpoint of yellow light. Every now and then I could see a gull flutter sleepily between them. Their nests were clustered between the peaks and connected by fiber-optic cables; the gulls had developed a complex infrastructure that spanned the valleys and the peaks and the cliffs.

I left the ravine by the time the sun had begun to rise and found myself in another region of gray and beige flatlands. This half of Gull country was an electronics wasteland, with mounds of shattered hard drives and computer chips between eroded garbage spires and the hollow shells of tower desktops. Light bulbs crunched under my boots. Streams of sewage left the mountains and joined rivers towards the ocean. The sunrise shone red on the millions of cracked cell phone screens and cathode ray monitors spread amongst the flat screen televisions and Betamax players. There were rotary phones and refrigerators, washers and dryers; all were dispersed upon the landscape like desert rocks. Little whirlwinds brushed gap t-shirts and cardboard boxes through the air.

There was a small gray building in the distance to the east. I could just make out the dim reflection of the sunrise on its far off windows. It looked like it was near the coast; but It was in that moment of salvation that dozens — maybe thousands — of gulls appeared from the void and shrieked in circles above me. I don’t know what woke them. Maybe it was the smell of chocolate on my sweat. I had eaten enough in the cave.

I ran in the direction of the building, which was grey like a bunker and had small glass windows reminiscent of a prison. Dusty red awnings were hung above the door and the windows. A metal sign above the door read, “Hardee’s.” I went inside the Hardee’s and shut the door. Some of the gulls smashed against the windows. The glass was hard enough that two of them were knocked unconscious. The others flew up and circled above the building. One of them sat outside and stared at me through the glass with creased brows and a murderous gaze. I went through the kitchen to ensure the back door and the drive-through windows were locked and secured. Then I went to one of the tables and called [the thing I came on]. I could hear the gulls as I talked.

“I’m in a Hardee’s,” I said.

The [General Manager’s] speech came through the radio garbled and nearly incomprehensible. I moved from table to table hoping to get a better signal.

“I’m in a Hardee’s,” I repeated endlessly over the tiny blue radio. I was only able to get a decent signal by standing text to the cash register on top of the service bar.

When his voice finally came through clearly, he sounded surprised, “You’re in a Hardee’s?”

“Yeah,” I said. The gull was still watching me through the glass. “It’s on the northeastern bit of the island.”

“Are they serving anything?” he asked.

I looked at the counter, “No…doesn’t look like it’s open really.”

“Huh,” he said. “Is there anything in the freezers?”

I checked the freezers. They were empty, “Nope. Looks like it’s been closed for a while.”

“Ah, well,” he said. “Did they lock the doors?”

“Nope.”

“You’d think they’d lock the doors.”

“They didn’t,” I said.

“We’ll try to be there as soon as possible. Don’t come out till we get there. We’ll come through the front.”

“That’s great,” I said, and moved to a booth and drew some doodles in my notebook.

[The thing I came on] arrived at the coast several hours later. [The people] on [the thing I came on] shot [fast moving metal projectiles] at the gulls with [things they held in their hands]. That scared most of them off. The others were were killed. I left the Hardee’s and got back on [the thing I came on]. [The people] on [the thing I came on] gave me a warm towel and a bunk for the night. They had made me sleep on the floor on the way to the islands.

Some Kind of Epilogue

Several days passed where I had only the ocean to confide in. I was eating ramen with some of [the people] on [the thing I came on]. One of [the people] asked, “So…uh…what’s with that jar of teeth you’re carrying around?”

“What?” I asked.

“The jar of teeth you have in your jacket.”

“Jar of teeth?” I asked. I felt for it in the breast pocket of my jacket. It was gone.

“[Bob] went about cleaning up your stuff while you were asleep,” [The man] said.

“Oh that? That was Herb’s,” I said. “I think he’s dead. He’d want his son to have it I guess.”

“What makes you say he’s dead?”

“A gull flew through his head,” I said.

“Through his head?”

“Yeah,” I said, and mimed it with my hands. “Through his head. In one side and out the other. It was crazy.”

[The man] shrugged, “How was the B.M.T.?”

*The contents of this story may or may not be 99% fictional. Though the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is a real place, its depiction in this article might be fictional. All characters in this work might be fictional. Any resemblance to individuals living or deceased could be entirely coincidental.